We've been hearing more in recent days about employers' challenges finding workers. Over the past week, we've teamed up with the Office of Economic Analysis to publish a summary of reasons Oregon's labor market is tighter than you might think.

The pandemic recession -- just like all economic downturns -- is unique. During this recovery labor demand remains strong. At the same time, several simultaneous factors are constraining the supply of labor for those job openings. They include:

1. Concentrated Nature of the Shock

Last spring, many businesses with similar labor pools shut down overnight. The economy experienced record-setting job losses and the unemployment rate increased nearly 10 percentage points in April 2020 alone. Those who remain unemployed are also largely on temporary layoff. In the previous recessions, the job losses were largely permanent, and the economic nadir did not occur until more than two years into each cycle, so businesses hiring during the recession and recovery had excess labor supply for a while. During this recovery the jobless numbers have dropped much faster.

Oregon’s unemployment rate matched the nation’s at 6.0% in March, below the average of 6.8% over the past two decades. Currently, hiring employers are facing a typical or slightly lower-than-typical available labor pool for their job openings. The available labor force is not evenly distributed either. While all sectors lost jobs in the initial COVID downturn, some have bounced back rapidly or hit new employment highs (such as transportation, warehousing and utilities, and professional and technical services). Depending upon the types of jobs employers are hiring for, there may be no excess labor.

2. Pandemic Concerns

The unemployment rate doesn’t include would-be workers who are out of the labor force, meaning they neither have a job, nor are they looking for one. Supplemental information from households in the Current Population Survey shows an estimated 45,000 people in Oregon said they were prevented from looking for work due to COVID-related reasons during the first quarter of 2021. While vaccinations have accelerated, only about half the adult population has received at least one vaccine dose for COVID-19 as of mid-April. COVID case counts are also rising in many areas of Oregon again this spring.

3. Lack of In-Person Schooling

Heading into the pandemic, one out of every six Oregonians in the labor force had kids, worked in an occupation that cannot be done remotely, and also did not have another non-working adult present in the household, according to research from the Office of Economic Analysis. As of mid-April, three-fourths of Oregon’s K-12 schools have students learning remotely from home either part- or full-time, according to Oregon Department of Education records.

Even with the anticipated return of full-time, in-person learning for the 2021-2022 school year, child care slots, which were already too scarce in most areas of the state prior to the pandemic, and summer programs will likely continue operating with reduced capacity for some time. These constraints limit workforce options for some parents of younger children.

4. Federal Aid and Unemployment Benefits

Total personal

income in Oregon today is about 15% higher than before the pandemic.

Strong federal fiscal policy response via recovery rebates alone added

$12 billion to personal income in Oregon. Although this has brightened

the overall economic outlook, a stronger safety net where incomes are

higher today than pre-COVID can temporarily reduce labor force

participation in the short term for some workers.

Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC) adds $300 onto weekly unemployment insurance benefits through September 4, 2021. In the first quarter of 2021, the weekly regular unemployment (UI) benefit has averaged $370 per week. With the additional $300 FPUC payment, that adds up to an average payment of $670 per week. That’s roughly the same as earning $16.75 per hour for someone working full time. During the first quarter of 2021, that has also represented full wage replacement (between 100% and 104%) relative to regular UI claimants’ pre-pandemic earnings on the job.

Some perspective here: earning $670 per week, working year round would total $34,800 in gross earnings for a worker. By comparison, the median earnings for full-time workers in Oregon in 2019 was $50,712. With “Now Hiring” signs in many business windows and stronger wage offerings as employers compete for available workers, it’s unlikely that this benefit, in itself, is keeping a vast number of workers on the sidelines.

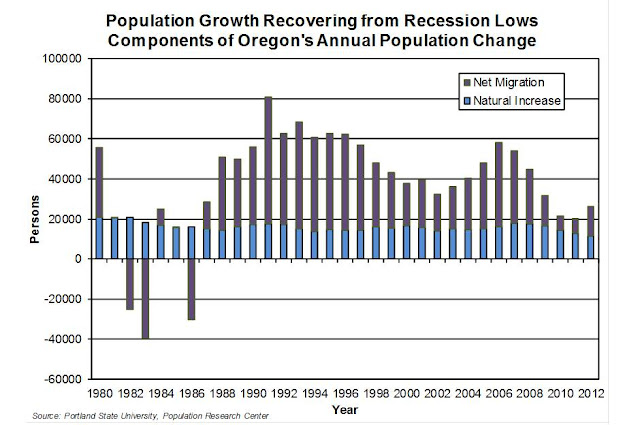

Last but not least, Oregon has a long-running record of adding labor force through net in-migration of workers from other states and areas. While Oregon continued to attract migrants in 2020, net migration fell to its lowest level since 2013 in Oregon, and was 20% lower at 28,600 than in 2019.

More information on Oregon's current labor market dynamics can be found in the full article and OEA blog post, written by State Economist Josh Lehner and State Employment Economist Gail Krumenauer.